the bamboo hut

Engineering the Impossible

By: Kay Gozon Jimenez

At 96, Angel Lazaro, Jr. is still dreaming of what may seem impossible to others, but is very realizable to him.

Over nearly 80 years, he has planned and built huge government and private projects that demonstrated his skills as an architect, environmental planner and civil, structural and hydraulic engineer. He master planned and designed the Bataan Export Processing Zone (BEPZ), government edifices, medical centers, the Baguio Bokawkan-Trancoville flyover, a broadcasting complex, public markets, ports, bridges and school buildings, as well as the restoration of six 400-year-old national heritage churches.

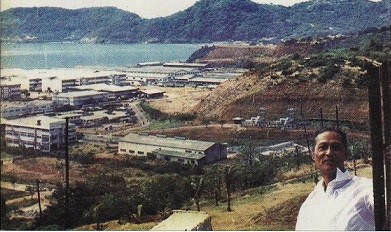

Lazaro considers as his most meaningful project the BEPZ, a 1,600-hectare industrial estate in Mariveles, Bataan which was practically a new city in the early 1970s. It was the first of several processing zones – he also did the Mactan and Baguio zones – which are now the backbone of foreign investments in the Philippines.

He recalls that he was asked to propose a master plan and design for the BEPZ. Three days after he presented his plans, Bureau of Customs Commissioner Rolando Geotina handed him a check and said: “This advance check is only money, we need plans.”

Lazaro was dumbfounded. “He just gave me the biggest A & E project of my life, with not even a cup of coffee involved.”

The 101st Construction Brigade of the Armed Forces of the Philippines assigned a courier at Lazaro’s office to immediately bring to Mariveles any plan he made. “I could not afford to make mistakes even if there were no calculators, computers or programs at that time, only slide rules and books,” he recalls.

The first order I gave was to build three new rivers. Mariveles, Bataan then was all mud and forest. There were three rivers criss-crossing the area. We buried these rivers, piling soil and rock seven meters deep, and we built three new rivers that ran in a straight line,” he says. “I designed thousands of buildings in the area – low-cost housing for 1,000 families, a hospital, a dormitory with 1,000 beds. I planned all electrical, water supply and drainage systems and installed an electrical system underground.”

Another project he is very proud of is a bamboo hut he designed for my bamboo farm in Antipolo, Majent Agro-Industrial Corp./Carolina Bamboo Garden which runs a bambusetum.

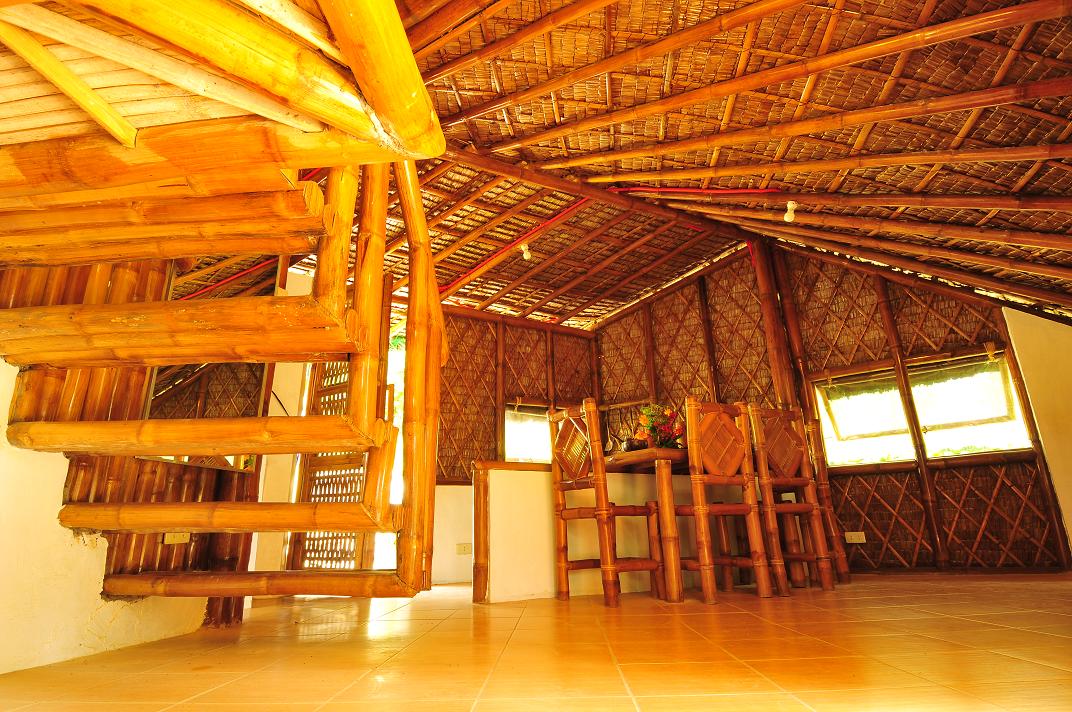

The two-storey hut stands on a hill within the 5-hectare farm. All the floors are equilateral triangles, and the roof is a saddle-shaped hyperbolic paraboloid, which Lazaro says is produced by a rod traveling along two non-intersecting straight lines. This is useful in analyzing the distribution of stresses for different forms of loading.

Bamboo doors are connected by rattan or nylon strings and natural light passes through the doors. The walls, made of pawid, let air circulate freely, as do the flooring and ceiling made of patpat. The beds, or papags, are made of bamboo poles. The ground floor material is tiles, while that of the second floor is finely chiseled strips of bamboo.

The roof is covered with a green fishing net to prevent birds from building nests on it, and protect from strong winds during typhoons. Plastic sheets are wrapped around the window frames to keep the pawid in place. The windows open with the traditional tukod, also made of bamboo.

There is a cantilevered – both horizontally and vertically – bamboo stairway leading to the second floor, with each step or railing able to carry a load of 250 lbs. with hardly any vibrations. It is probably the only stairs which every step is structurally analyzed and designed.

Carolina Bamboo Garden grows 35 varieties of bamboo. It has become a mecca for environmentalists and individuals interested in growing bamboo for livelihood and for constructing houses. CBG propagates seedlings that are sold, and in some cases, distributed free among school children and farmers. People attending seminars in the farm come from all over, even as far as Qatar.

Aside from its unique beauty, the kubo is inexpensive to build. According to Lazaro, the hut is composed of 60 per cent bamboo, all harvested from the farm; 20 percent nipa shingles, 15 per cent concrete hollow blocks and five per cent miscellaneous materials. If the bamboo is self-grown and the house is built by the family, construction cost should be less than P25,000, says Lazaro.

The kubo has modern amenities, such as a radio, two-way switches, a doorbell, shower and bath, metered electricity and water, and a chimney through which warm air from human bodies and cooking rises, thereby inviting the cold, clean heavier air in – the chimney effect.

Lazaro had actually built in 1965 a similarly shaped kubo in his fishpond in Malabon, but using wood and cement. The structure looked so unusual that fishermen who passed by in their boats kept looking at it and bumped into the dikes.

Lazaro vouches for the durability of bamboo houses. He says that all the low-cost houses and 1,000-bed dormitories built in 1973 with concrete hollow blocks and reinforced with bamboo in the BEPZ are still standing today.

One can vary the kubo by changing the roof from pawid to corrugated G.I. sheets or even tiles. The purlins can be changed from bamboo to wood or steel. Even if the roof surface is beautifully curved, it is still generated by a straight line and will therefore accept any roofing that can be placed on one-dimentional surfaces. The bamboo posts and beams can be changed to wood or steel.

But why change the indigenous materials? Lazaro says bamboo houses built 30 years ago are still intact, cool and very inviting. To prevent infestation by termites, he treats the bamboo materials with sea water.

Lazaro also painstakingly designed a 195-step “stairway to heaven” at whose top is a small chapel from where one has a splendid view of forests. He says: “Of all my designs, I am proud of the bamboo hut. It takes a lot of brain to produce it.”

Lazaro was valedictorian of his class in Malabon Standard High School. There was no salutatorian, as the next highest had a grade point average way below his.

His father, Angel, Sr., was a justice of the peace in Obando, Bulacan. His salary was small, but he gave it away to needy people. His income came from the produce of his small fishpond; from it he was able to design and build the only three-storey house in Malabon at that time. He designed his house with glass and frames bearing the likeness of the red/white/blue Philippine flag. At Rizal Day parades, he would place a paper mache ant on top of a float. The ant, he said, was a symbol of the Filipino; though small, it would not let go but bite until it died.

His mother Eduvigis taught him to love God. But everything about love of country came from his father, who used to tell his son: “When you love your country, you do not love the soil or the mountains, you love people, your countrymen.”

He enrolled in civil engineering at Mapua, but soon realized he really wanted to be an architect. But since he would lose his scholarship if he shifted courses, he finished the civil engineering course. Years later he took up architecture at National University.

He worked both as a civil engineer and an architect, winning highly coveted awards, and was elected national president of both the Philippine Institute of Civil Engineers (PICE) and the United Architects of the Philippines (UAP).

While he was in the US, Lazaro pursued a masters in civil engineering, major in hydraulics, minor in structural engineering, at the University of Iowa. He won second prize (with a cash award of $5,000) in the International Bridge Design Competition sponsored by Lincoln Arc Welding, with 37 countries participating.

He had also completed all the requirements for a master of science in higher mathematics at the University of the Philippines, but did not receive a diploma on account of the breakout of the Second World War.

In 2012, at age 94, he was cited as one of the 50 Most Outstanding Civil Engineers in the country. That same year, he was honored by the Philippine Institute of Architects-United Architects of the Philippines (PIA-UAP) with Gintong Likha award. He was conferred the title of Doctor of Technology, honoris causa, by his alma mater, National University. Earlier this year, he was awarded the title ASEAN Architect by the ASEAN Monitoring Committee.

At 96, does he still have projects to do? “Yes,” he answers, his eyes twinkling. “I am looking for a cure for cancer, using architectural and engineering points of view, and I have already written the first 30 pages of a book on this.”

Without being pressed to explain, he asks, “Who were the people who invented the machines for taking blood pressure, radiation and X-ray? Not medical doctors, but engineers.”

He also has four different complete solutions on how to eradicate corruption – “but this is another long story.”

Back view of Bahai Kubo

The roof is covered with a green fishing net to prevent birds from building nests on it, and protect from strong winds during typhoons.

View facing the entrance from inside the Bahai Kubo

Hanging stairs at Bahai Kubo

There is a cantilevered – both horizontally and vertically – bamboo stairway leading to the second floor, with each step or railing able to carry a load of 250 lbs. with hardly any vibrations. It is probably the only stairs which every step is structurally analyzed and designed.

Stairway to Heaven

Lazaro also painstakingly designed a 195-step “stairway to heaven” at whose top is a small chapel from where one has a splendid view of forests.

The Bataan Export Processing Zone is one of Lazaro’s most meaningful projects.

The architect with his family